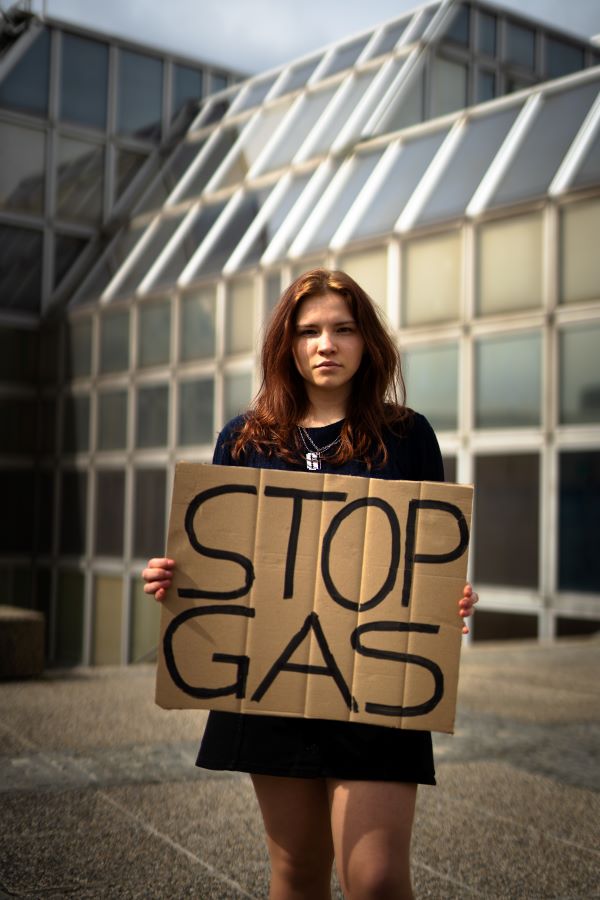

Valeriia Bondarieva is a 22-year-old climate activist currently living in Kyiv, Ukraine and she is the co-founder on Rozviy Youth Climate Initiative. She is a translator with a background in working with texts related to politics, sociology, environment and energy. She stopped by in the Turkish metropolis Istanbul on her way to United Nations Climate Summit (COP27) held in Egypt last year, and we had the opportunity to meet face to face briefly.

Atlas Sarrafoğlu: How did you start activism and how did you organize your strikes in Ukraine before the war broke out?

Valeriia Bondarieva: Here’s a funny fact: I started as a kid who would refuse to talk to her friends when they would throw trash in the street. It’s because I had seen a lot of footage of pollution on the TV or the Internet and was really scared of the scale of what we were doing to our nature. My parents’ friends would even call me “young Greenpeace”. However, things turned pretty serious when in the last year of school, several girls and I formed a team and competed in the Technovation Challenge, where we presented our app: It was a habit tracker promoting an environmentally friendly lifestyle. We continued working on this start-up for one and a half more years. We had potential sponsors, but eventually it didn’t work out as we all entered universities and, thus, happened to live in completely different parts of the world.

I joined my first climate strike in the spring of 2019, when the Fridays For Future (FFF) movement was only unfolding. It was the first year of my studies at the university in Kharkiv, and a new friend of mine, whom I met at a random vegan party, invited me there. At the time, I didn’t know anything about climate change except for the fact that it existed. Later, I joined the local organizing group, and in the summer visited my first international FFF meeting in Lausanne. That’s when my world shook. Now, you can see why: moving from emphasizing individual responsibility to recognizing the systemic nature of the problem, which therefore required our collective fight.

But things weren’t going smoothly. The issue of climate change wasn’t deemed serious by the population and thus the government. I remember that the maximum number of people we managed to gather was around 70 at one of our strikes. I got frustrated, but I could actually relate to people. At the time, I still didn’t know much, which is why I got the idea to organize a one-month climate school. The national group liked it. So, in autumn 2021, we shifted our focus to climate education and, alongside our strikes, started working on this project together with the UNICEF [United Nations Children’s Fund]. The school was supposed to be launched in spring 2022. But, as you may have guessed, it didn’t happen.

Embargo campaign against Russian fossil fuels

The year 2022 marked a significant shift in my activism, as now I got involved in international work. Together with other Ukrainians and Eastern Europeans, I began advocating for an embargo on all Russian fossil fuels that were funding Russia‘s war machine. And yeah, it was a difficult year filled with hopelessness and despair, but it was also a year of building a new community and exploring the intersection of climate, human rights, and peace.

How is the climate crisis affecting people’s lives in general and what is the direct impact of climate change in Ukraine?

We are all well aware that Russia aggravated the global food crisis by occupying the fertile southern region of Ukraine, by mining or bombing arable fields and, of course, by blocking Ukraine’s Black Sea ports, which had been crucial for exporting grain and oilseeds worldwide. While these events are not directly linked to climate change, they have highlighted Ukraine’s role as one of the world’s largest breadbaskets.

I also recall the anxiety I experienced last year when many products typically cultivated in southern and eastern Ukraine became scarce, with their prices soaring. For example, you surely know the Kherson region, where the Khakhovka dam was blown up this June. Before the occupation, the Kherson region alone contributed to 12 per cent of Ukraine’s total vegetable harvest, including eggplants, tomatoes, watermelons, cucumbers, peppers, and zucchinis.

So, indeed, Ukraine is highly dependent on the agricultural sector. In 2021, it contributed approximately 10.7 percent to the country’s Gross Domestic Product. What does it mean? Ukraine is, therefore, highly vulnerable to adverse effects of climate change. One of the obvious ones is reduced rainfall, which results in droughts that are already impacting our crop yields. With average temperatures breaking records each year, Ukrainians can only anticipate more food shortages, along with exacerbation of consequent economic and social challenges.

It is also important to mention that Ukraine is the least water-supplied country in Europe. Thus, less frequent rains will only worsen water shortages because there will not even be enough water to redirect from rivers to man-made reservoirs.

Another important concern is health. Many Ukrainians are struggling with physical and mental health issues, which have become more difficult to manage because of the war. Sadly, the heatwaves increase the risk of worsening heart and cardiovascular problems in general. For example, those who live with heart conditions already will be more prone to heart failure. Increased flooding due to climate change in Ukraine, will lead to more incidence of hepatitis A, cholera and salmonellosis, further exacerbating health vulnerabilities.

Climate activism amid ongoing war

How does the war affect your fight against the climate crisis?

It is hard to talk about climate change as a concern when there’s a more immediate threat to our lives. In the first month of the full-scale invasion, I was completely devastated and, actually, frustrated about all the time I had dedicated to climate activism. Because how was I so naive to worry about something so distant to me as the climate crisis when there had been the eight-year Russian occupation posing a much bigger threat all along?

On the other hand, actually, climate activism helped me pull through my depressed state. When negotiations regarding an embargo on all Russian fossil fuels began, I realized that I could play my part in our victory by sticking to what I knew best: fighting against fossil fuels. But now it has been on a whole new level as I’ve learnt, and still am, about how fossil fuels contribute to human rights abuses and cause so much turmoil in the world, apart from driving environmental catastrophes. And this is something I wish more people could understand: The climate crisis is so deeply intertwined with various political, economic, and social processes, that it is more than just a matter of caring for nature.

I think Ukrainians are somewhat familiar with this interconnection. In the past year and a half, we have been discussing a lot that Russia uses its revenues from fossil fuel exports to fund the war in our country, that the war contributes to climate change, or that climate aspirations are essential for our European Union (EU) integration. I mean this is good that we talk about it, isn’t it? Well, here’s a thing: To my mind, it works completely well as long as we genuinely recognise climate change as a dire issue rather than simply exploiting it for the sake of our interests. Without this actual recognition, I am afraid it’s simply used to prove the narrative that Russia is bad and we are worthy of entering the EU. I am afraid that instead of showing the climate change as a complex thing, it’s being oversimplified to spread the narrative easily but not to encourage people to explore further, as it’s not seen as a pressing concern when compared to highlighting the consequences of Russia’s war crimes.

I find this problematic only because it doesn’t really help to get people on board with climate activism. Sad but true, actual climate issues do not resonate with the majority of Ukrainians for obvious and understandable reasons. This underscores the concept of climate injustice: communities impacted by wars or conflicts often have other more urgent things on their plate and therefore are left with limited capacities and resources to tackle the climate crisis.

Luckily, there is an alternative approach to engage Ukrainians. People want not only to rebuild but to build better, and our mission is to demonstrate that this improved version can’t be truly better unless it’s done in an environmentally sustainable way. While this collocation may appear as a buzzword, for me, it does encompass a wide range of environmental, economic, and social aspects essential for creating a stronger Ukraine. Moreover, if we, Ukrainians, are to uphold our image as a people who knows what true peace looks like, we need to be truly committed to supporting social and climate justice. But this is a very nuanced topic due to our current political vulnerability.

We are seeing a political environment that is becoming more and more hostile to activists. How is the situation in Ukraine?

It is hard to judge, as protests are not allowed during the martial law period, though some of them do occur from time to time. It is our constitutional right, after all. However, talking particularly about climate activists, it is clear that the political environment inevitably influences how their protests and actions are portrayed in the international media. Often, the image of climate activists is negative. And this is something I am concerned about in Ukraine as our media have every opportunity to adopt a similar discourse if those persist. While I do believe that there are many examples of professional journalism that highlight the perspective of the protesters, I’ve also come across a couple of Ukrainian articles that, at least to me, seem manipulative in depicting climate activists as mere radical youths who don’t know what they’re doing.

Why is it such a big concern for me? Because it is also a very big question of what our recovery process will look like. Without any doubt, the energy sector will be an integral part of it, and so here’s what we need to decide on: Will we be extracting more fossil fuels, or will we switch to renewables and other sources? I often talk about a just green energy transition in my bubble, which makes it seem that there is progress towards climate goals; but there have also been ongoing negotiations between our state energy company, Naftogaz, and our ‘best-loved’ Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Halliburton. I am quite certain that if they are to expand their presence in Ukraine, they will be the ones interested in discrediting climate activists to prevent actions against them. This is just my assumption but it is something I want to be prepared for.

Greta’s impact

What is the perception of your government regarding tackling the climate crisis?

Given that climate change is a top priority for Ukraine’s strategic allies, especially the EU and the United States (US), we certainly want to demonstrate that we don’t fall behind and acknowledge the climate crisis as a pressing threat that needs to be addressed. So I feel that there is actually a noticeable shift in the narratives regarding our commitment to climate goals.

A very good example would be Greta Thunberg‘s visit to Kyiv as part of the International Working Group on environmental war crimes this June. Before the meeting, it’s highly unlikely that anyone in the government paid much attention to Fridays For Future Ukraine and our demands. However, now we were invited, specifically by the Office of the President and the Ministry of Environmental Protection, and later even received a positive response to one of our letters. Frankly speaking, at this stage, I view such events or actions as a way to maintain an image of a progressive state. But it isn’t necessarily a bad thing because it regularly brings up the issue of climate for the public to hear and discuss.

Of course, it’s true that the EU and the US aren’t always consistent in their policies, and our perception may not have changed completely. However, it was important for me to briefly share something that offers a glimmer of hope, as now I feel that climate is taken even more seriously today in Ukraine.

Do you feel hopeful that we will tackle the climate crisis?

Honestly, with everything going on in the world and tensions rising, I have been struggling with keeping hopeful. And while I believe it’s a valid reaction, it’s also important not to let it consume me entirely. I love rewatching Christiana Figueres’s fabled TED Talk, where she talks about the importance of optimism in tackling the climate crisis. For her, keeping optimistic is about “courage, hope, trust, solidarity, the fundamental belief that we humans can come together and can help each other to better the fate of mankind.” And it deeply resonates with me because the main thing that keeps me going is working with people from various segments and sectors of our society. I genuinely enjoy it; it is indeed comforting to know that there are many individuals who dedicate their time to making society function and, in fact, improving it. Especially when it comes to Ukraine, the country I plan to live in for my entire life, and so, it is in my interest to ensure a safer and promising tomorrow.” I am glad to see that I am not alone in this; there are so many Ukrainians working in different fields for our better future.

Therefore, our activist narratives should always emphasize the opportunity to prevent the worsening of the current crises, including the climate one, rather than descending into doomerism, which only discourages action. I feel a responsibility to maintain hope and carry on. And even though our contributions may sometimes seem small, at the end of the day, they do play a crucial role in our broader societal progress.

Lastly, I would like to quote my fellow climate activist Dominika Lasota, who in one of her interviews said, “Victories are still possible”. Together with her colleague, Wiktoria Jędroszkowiak, they worked a lot on encouraging women and the youth to come to vote at this year’s parliamentary election, and they succeeded: The opposition did beat the conservative and nationalist ruling party of eight years. Now, there’s a greater glimmer of hope for climate action in their country. I truly admire how their belief in change drove them, and I think this was what made their work a win. Victories are still possible.

Lastly, I would like to quote my fellow climate activist Dominika Lasota, who in one of her interviews said, “Victories are still possible”. Together with her colleague, Wiktoria Jędroszkowiak, they worked a lot on encouraging women and the youth to come to vote at this year’s parliamentary election, and they succeeded: The opposition did beat the conservative and nationalist ruling party of eight years. Now, there’s a greater glimmer of hope for climate action in their country. I truly admire how their belief in change drove them, and I think this was what made their work a win. Victories are still possible.

For better Ukraine

What is your perception of the future in regards to the climate crisis? How do you envision yourself in 2030?

Again, this is a conversation about our hope. In a report, released this spring, the World Meteorological Organisation stated that “there is a 66 per cent likelihood that the annual average near-surface global temperature between 2023 and 2027 will be more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels for at least one year.” This is something I began my activism with: demanding from our governments to prevent this global temperature rise, as they themselves agreed to do in the 2015 Paris Agreement. And now, we observe that it is actually likely to happen, plus sooner than expected. Another factor is that, with all the ongoing global political tensions, there are significant setbacks for our climate goals, as other, often short-term, priorities take precedence.

I definitely believe that the climate race among countries, especially the wealthier ones, will play its role in how committed they will be to maintaining their climate goals. All in all, this decade is considered decisive, with many pivotal decisions still yet to be made in the coming years. We must watch closely what these decisions will be, however.

As for myself in 2030, I am still uncertain. There has been a lot of change in my life in the past year, which led my climate colleague, Viktoriya Ball and me to establish our own youth climate initiative called ‘Rozviy‘ (Ukrainian for ‘flourishing’ or ‘thriving’). Despite the brutal and turbulent times, we tap into our hope for a better Ukraine through our climate activism. Alongside other Ukrainian and Eastern European activists, we advocate for green and just energy transition as well as food systems transition, cherishing our ambition to emerge as a stronger country and region, guided by the principle ‘building back better’. This requires a radical and transformative shift towards economic, environmental and social sustainability. While it is overly optimistic to expect all these changes by 2030, I hope the main processes will get the ball rolling; we just need to be a little bit more persistent about it. ;)

*

Social media accounts

X/Twitter: BondarevaValera

Instagram: valeriia_bondarieva